The Guru of Disruption’s Last Word

A truly great man passed away this last weekend, Professor Clayton Christensen, author of the bestselling “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” It seems that all my friends who met or knew him were influenced by this giant in the field of business books. His passing comes at a rather interesting (and disruptive) juncture for the world of business and quite frankly the future of our species, so I thought I’d make some additional comments after initially blogging at Quartz.

The word disruption exploded in popularity in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/9. You had Techcrunch name a conference after it, Marc Andreessen warned that software disruption would eat the world and the Paypal founder and investor Peter Thiel said it was one of his favourite words. Practically everyone I met in California when I was venture investing there in the last decade would talk incessantly of disruption. As I previewed in my recent blog, I’m also expecting the next decade to be quite ‘disruptive’ with immense change in the pipeline.

Professor Christensen’s Definition of Disruption

Prof Christensen, however, thought the word ended up becoming overused and not as he originally intended. The Innovator’s Dilemma in his mind was that company managers could actually fail by successfully doing 2 things that they were actually taught to do at business school : first to listen to their most important clients and second to focusing on investments on innovation which promised to have the highest ROI.Yet by doing the right things, these managers fail to see the next wave of innovation coming and get disrupted.

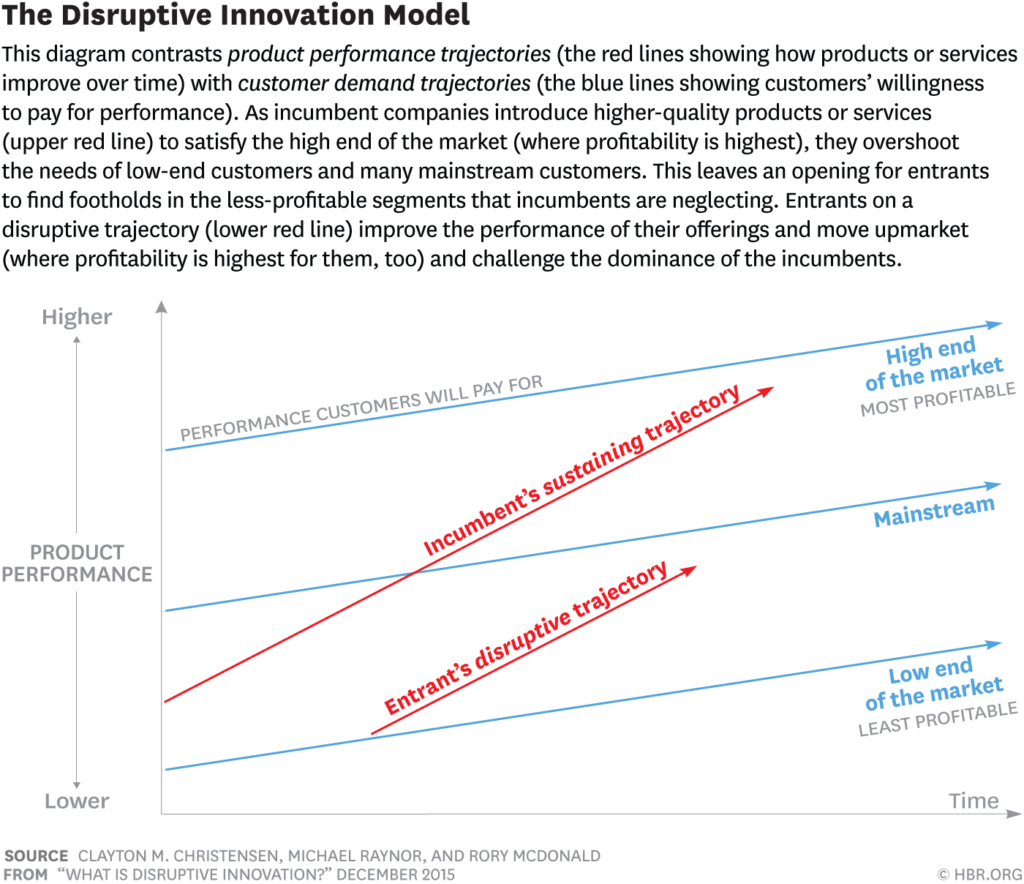

In his own words in a 2015 Harvard Business Review article, he and his co-authors write:

” ‘Disruption’ describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price. Incumbents, chasing higher profitability in more-demanding segments, tend not to respond vigorously. Entrants then move upmarket, delivering the performance that incumbents’ mainstream customers require, while preserving the advantages that drove their early success. When mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume, disruption has occurred.”

Business Legacy

This theory proved to be so true. In the field of business strategy, Prof Christensen is a real legend and many top leaders attribute their success to him. In a fabled meeting with Andy Grove, when the Intel CEO kept asking whether Intel was correct in investing in the low end but cheap Celium chip, he refused to tell them what to do. He said it was more important for him to explain the theory, to tell them HOW to think but not WHAT to think. In the end, Grove attributed Christensen with guiding him to making the correct decision.

Netflix based a lot of their strategy on his work. Remember they started out in a very fringe business of mail order videos, whilst the massive incumbent Blockbuster didn’t think that they were a threat at all.

As the Professor describes:

“When Netflix launched, in 1997, its initial service wasn’t appealing to most of Blockbuster’s customers, who rented movies (typically new releases) on impulse. Netflix had an exclusively online interface and a large inventory of movies, but delivery through the U.S. mail meant selections took several days to arrive. The service appealed to only a few customer groups—movie buffs who didn’t care about new releases, early adopters of DVD players, and online shoppers. If Netflix had not eventually begun to serve a broader segment of the market, Blockbuster’s decision to ignore this competitor would not have been a strategic blunder: The two companies filled very different needs for their (different) customers.

However, as new technologies allowed Netflix to shift to streaming video over the internet, the company did eventually become appealing to Blockbuster’s core customers, offering a wider selection of content with an all-you-can-watch, on-demand, low-price, high-quality, highly convenient approach. And it got there via a classically disruptive path. If Netflix (like Uber) had begun by launching a service targeted at a larger competitor’s core market, Blockbuster’s response would very likely have been a vigorous and perhaps successful counterattack. But failing to respond effectively to the trajectory that Netflix was on led Blockbuster to collapse.”

The truth of business, especially technology companies, is that you will eventually become blind-sided if you are not careful.

More Important Legacy – Purpose

As we enter a new decade, potentially quite a disruptive decade (in the wider sense of the word disruptive), the Professor had another important message. In fact, its one which I’ve been espousing for quite some time as a specialist in change.

I think Professor Christensen’s greatest legacy is probably his work emphasising having a life strategy, purpose. In an article in the HBR – “How Will You Measure Your Life” – he writes:

“Over the years I’ve watched the fates of my HBS classmates from 1979 unfold; I’ve seen more and more of them come to reunions unhappy, divorced, and alienated from their children. I can guarantee you that not a single one of them graduated with the deliberate strategy of getting divorced and raising children who would become estranged from them. And yet a shocking number of them implemented that strategy. The reason? They didn’t keep the purpose of their lives front and center as they decided how to spend their time, talents, and energy.”

He said that if you don’t have a clear purpose – and a way to measure whether you life is successful – then you’ll end up falling in to the trap of marginal cost analysis. People so easily will say to themselves, if I just do this I can make some extra money with little extra effort.

However, “if they don’t figure it out [their purpose], they will just sail off without a rudder and get buffeted in the very rough seas of life. ”

And this has been one of more core ideas when I give talks in the capacity of a futurist: the next decade will only get more disruptive (in the wider meaning) so its even more important than ever.The Professor also says that one should follow one’s North Star 100% of the time, this is easier than 98% of the time. He give an example when he was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford:

“I’d like to share a story about how I came to understand the potential damage of “just this once” in my own life. I played on the Oxford University varsity basketball team. We worked our tails off and finished the season undefeated. The guys on the team were the best friends I’ve ever had in my life. We got to the British equivalent of the NCAA tournament—and made it to the final four. It turned out the championship game was scheduled to be played on a Sunday. I had made a personal commitment to God at age 16 that I would never play ball on Sunday. So I went to the coach and explained my problem. He was incredulous. My teammates were, too, because I was the starting center. Every one of the guys on the team came to me and said, “You’ve got to play. Can’t you break the rule just this one time?”

When you make exceptions, you life could just become an “unending stream of extenuating circumstances.”

I really get that. It’s so easy to find exceptions. And its so tricky to maintain a direction . But when you enter very chaotic period, it really helps if you have a North Star. I have been very guilty in the past of forgetting my bigger mission and then doing some things for a little money (yes we all need to keep the lights on and put food on the table), because they were intellectually stimulating, before I was asked and didn’t want to turn someone down and the list goes on. Invariably I got less done, made less money and didn’t always feel good about the results.